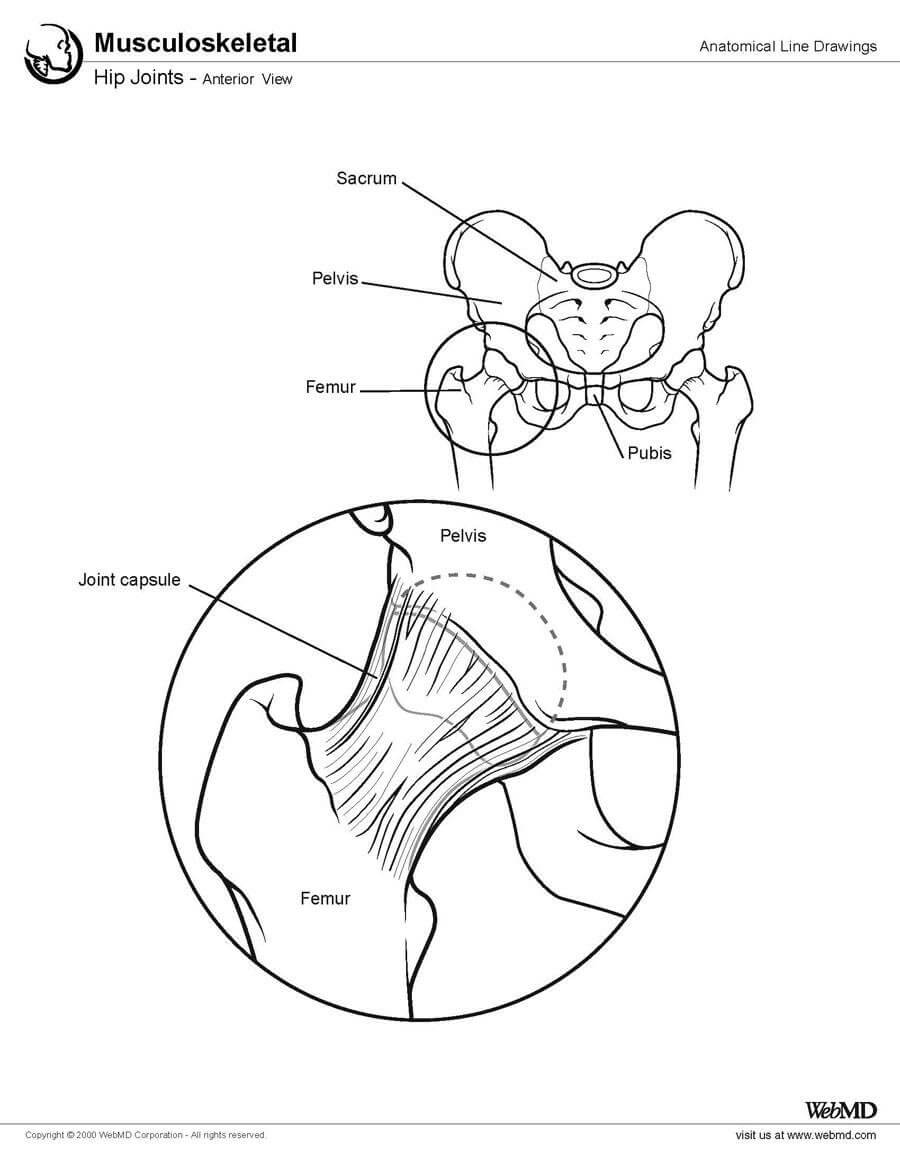

Hip Joint Anatomy

The hip joint (see the image below) is a ball-and-socket synovial joint: the ball is the femoral head, and the socket is the acetabulum. The hip joint is the articulation of the pelvis with the femur, which connects the axial skeleton with the lower extremity. The adult os coxae, or hip bone, is formed by the fusion of the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis, which occurs by the end of the teenage years. The 2 hip bones form the bony pelvis, along with the sacrum and the coccyx, and are united anteriorly by the pubic symphysis.

Hip Biomechanics

Hip biomechanics are quite complex due to pelvic motion associated with it and range of movements it produces.

During normal gait, on heel-strike, the hip moves into 3o degree of flexion and at toe-off [when the foot is finally off the ground] about 10° of extension. The range of abduction to adduction is about 11°, and for internal-external rotation, the range is about 8°.

During different phases of gait cycle, different forces act on femoral head. Approximately two thirds of the hip force is produced by the abductors.

The directions of the resultant force on the joint are important to the function of total hips.

It is useful to consider the forces relative to axes based on the long axis of the femur.

In the coronal plane the forces acting make an angle of 15° to 27° to the long axis of the femur during stance phase of gait which results in axial compression, varus and mediolateral forces. In the saggital plane, anteroposterior forces on the femoral head,result in torsion.

The latter has significant role in the compressive failure of trabecular bone in uncemented stems and resulting in stem fractures.

Femoral offset often influences the mechanics of the hip. Femoral offset id often reduced in normal total hip replacement. This results in an increase in the required abductor force leading to a higher resultant joint force and sometimes a gait abnormality. An increase in offset would reduce the force but causes an increase in the bending moment on the stem.

Hip Biomechanics – Forces Acting on the Hip

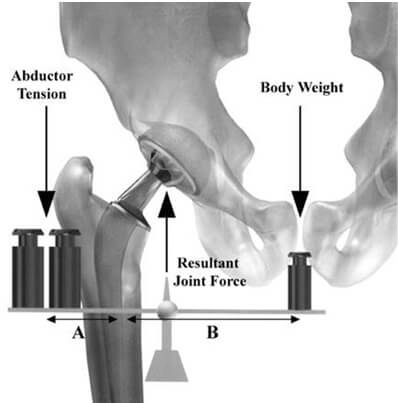

The body weight can be taken as load applied to a lever arm extending from the body’s center of gravity to the center of the femoral head. The abductor mechanism acts on the lever arm extending from the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter to the center of the femoral head.

This force by abductors must be equal to the load applied by weight to hold the pelvis level when in a one-legged stance and a greater moment to tilt the pelvis to the same side when walking.

The ratio the length of the lever arm of the body weight to that of the abductor musculature is about 2.5 : 1. Therefore the force needed by abductor muscles must approximate 2.5 times the body weight to become equal to the force applied by body weight.

The estimated load on the femoral head in the stance phase of gait is equal to the sum of the forces created by the abductors and the body weight and is at least three times the body weight.

In earlier days of Charnley, a concept was introduced to alter the length of lever arms. This was done by deepening the acetabulum and by reattaching the osteotomized greater trochanter laterally. This would result in decrease in the moment produced by the body, and the counterbalancing force that the abductor mechanism must exert is decreased.

The abductor lever arm may be shortened in arthritis, supratrochanteric shortening, external rotational deformities, and in many patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip.

In current practice of hip replacement altering the lever arm is not practiced. The stress is on preservation of the subchondral bone and to deepen the pelvis only as much as necessary to obtain bony coverage for the cup. Most total hip procedures are now done without osteotomy of the greater trochanter.

The basic goal is to preserve subchondral bone and to avoid problems related to reattachment of the greater trochanter.

In the saggital plane, the forces act to bend the stem posteriorly and become more pronounced when the hip is flexed. It has been found that the joint reaction force was lower when the hip center was placed in the anatomical location compared with a superior and lateral or posterior position.

Not everyone with hip arthritis is a candidate for total hip replacement surgery. Below are lists of indications and contraindications for this surgery.

Indications for Total Hip Replacement Surgery

Patients eligible for this surgery have moderate to severe arthritis in the hip, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis or post-traumatic arthritis, that causes pain and/or interferes with daily living. For example:

- Walking, going up stairs, and bending to get in and out of chairs is difficult

- Pain is moderate to severe even while resting, and may affect sleep

- Joint degeneration has caused stiffness that affects the patient’s range of motion during normal activities; the patient may also have a limp

- Symptoms are not adequately alleviated by non-surgical treatments, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, steroid injections, or the use of a cane or walker.

About 90% of patients who undergo hip replacement have hip osteoarthritis.7 In addition to arthritis, some patients have hip replacement surgery to correct problems related to fractures (i.e. a "broken hip") or other medical conditions, such as osteonecrosis (bone death caused by inadequate blood supply).

What Is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis, commonly known as wear-and-tear arthritis, is a condition in which the natural cushioning between joints -- cartilage -- wears away. When this happens, the bones of the joints rub more closely against one another with less of the shock-absorbing benefits of cartilage. The rubbing results in pain, swelling, stiffness, decreased ability to move and, sometimes, the formation of bone spurs.

Who Gets Osteoarthritis of the Knee?

Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis. While it can occur even in young people, the chance of developing osteoarthritis rises after age 45. According to the Arthritis Foundation, more than 27 million people in the U.S. have osteoarthritis, with the knee being one of the most commonly affected areas. Women are more likely to have osteoarthritis than men.

What Causes Knee Osteoarthritis?

The most common cause of osteoarthritis of the knee is age. Almost everyone will eventually develop some degree of osteoarthritis. However, several factors increase the risk of developing significant arthritis at an earlier age.

- Age : The ability of cartilage to heal decreases as a person gets older.

- Weight : Weight increases pressure on all the joints, especially the knees. Every pound of weight you gain adds 3 to 4 pounds of extra weight on your knees.

- Heredity : This includes genetic mutations that might make a person more likely to develop osteoarthritis of the knee. It may also be due to inherited abnormalities in the shape of the bones that surround the knee joint.

- Gender : Women ages 55 and older are more likely than men to develop osteoarthritis of the knee.

- Repetitive stress injuries : These are usually a result of the type of job a person has. People with certain occupations that include a lot of activity that can stress the joint, such as kneeling, squatting, or lifting heavy weights (55 pounds or more), are more likely to develop osteoarthritis of the knee because of the constant pressure on the joint.

- Athletics : Athletes involved in soccer, tennis, or long-distance running may be at higher risk for developing osteoarthritis of the knee. That means athletes should take precautions to avoid injury. However, it's important to note that regular moderate exercise strengthens joints and can decrease the risk of osteoarthritis. In fact, weak muscles around the knee can lead to osteoarthritis.

What Are the Symptoms of Knee Osteoarthritis?

Symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee may include:

- pain that increases when you are active, but gets a little better with rest

- swelling

- feeling of warmth in the joint

- stiffness in the knee, especially in the morning or when you have been sitting for a while

- decrease in mobility of the knee, making it difficult to get in and out of chairs or cars, use the stairs, or walk

- creaking, crackly sound that is heard when the knee moves

- Other illnesses. People with rheumatoid arthritis, the second most common type of arthritis, are also more likely to develop osteoarthritis. People with certain metabolic disorders, such as iron overload or excess growth hormone, also run a higher risk of osteoarthritis.

How Is Osteoarthritis of the Knee Diagnosed?

The diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis will begin with a physical exam by your doctor. Your doctor will also take your medical history and note any symptoms. Make sure to note what makes the pain worse or better to help your doctor determine if osteoarthritis, or something else, may be causing your pain. Also find out if anyone else in your family has arthritis. Your doctor may order additional testing, including:

- X-rays, which can show bone and cartilage damage as well as the presence of bone spurs

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans

MRI scans may be ordered when X-rays do not give a clear reason for joint pain or when the X-rays suggest that other types of joint tissue could be damaged. Doctors may use blood tests to rule out other conditions that could be causing the pain, such as rheumatoid arthritis, a different type of arthritis caused by a disorder in the immune system.